Why it matters: Earlier this month, the US government blocked the sale of specific chips to anyone in China. We see this as an important change by the government in the tactics they are deploying. The United States has gone from blocking specific companies in China, to blocking all companies and focusing on specific products. This is a big change, and opens up the question – what exactly are they hoping to achieve? This matters obviously in that it can help us predict the outcome, but we increasingly hold the view that the government may not have entirely thought through how this will ultimately play out.

Some background. The US has been pushing back against China's trade practices, going back to the late Obama administration, with a marked escalation by his successor. The Biden administration appears to be maintaining that path, albeit with some rethinking of the tactics.

Until just recently, the US government had largely relied on its "Entity List" (here is the complete list), for those keeping score at home, there are 183 Huawei entities on the list. This blocks specific companies from purchasing products exported from the US, or produced by US companies and/or IP.

Editor's Note:

Guest author Jonathan Goldberg is the founder of D2D Advisory, a multi-functional consulting firm. Jonathan has developed growth strategies and alliances for companies in the mobile, networking, gaming, and software industries.

The entity list process is unlikely to be remembered for its success. As soon as a large number of large Chinese companies started appearing on this list around 2017-2018, US companies dispatched teams of lawyers and lobbyists to poke as many loopholes as they could.

From the Chinese perspective, the entity list appeared terrifyingly random. True, Huawei was a primary target, but many other companies ended up on the list for reasons not entirely clear to them. We have spoken with many people at Chinese companies who have grown incredibly wary of doing business with anyone in the US for fear that they will somehow end up on the list. This has created a high degree of uncertainty and a rush for alternatives, a topic which we will return to below.

Late last month, the US government added seven more names to the list, and judging from those names we have to question who is compiling this list. These latest additions all appear to be involved with aerospace matters, and while they have academic connections, the fact that all seven have Unit number designations seems to indicate that these are military affiliates, if not outright units of the People's Liberation Army (PLA).

We are now six years into this process, how are these units just now being added to the list? Judging by what came next, we have to think that the people putting the list together realized they faced a hopeless task. Chinese companies have become incredibly adept at creating byzantine corporate structures, making tracking their affiliations close to impossible. Our guess is that someone in the government realized the futility of this approach and made the decision to instead switch to banning shipments of specific products.

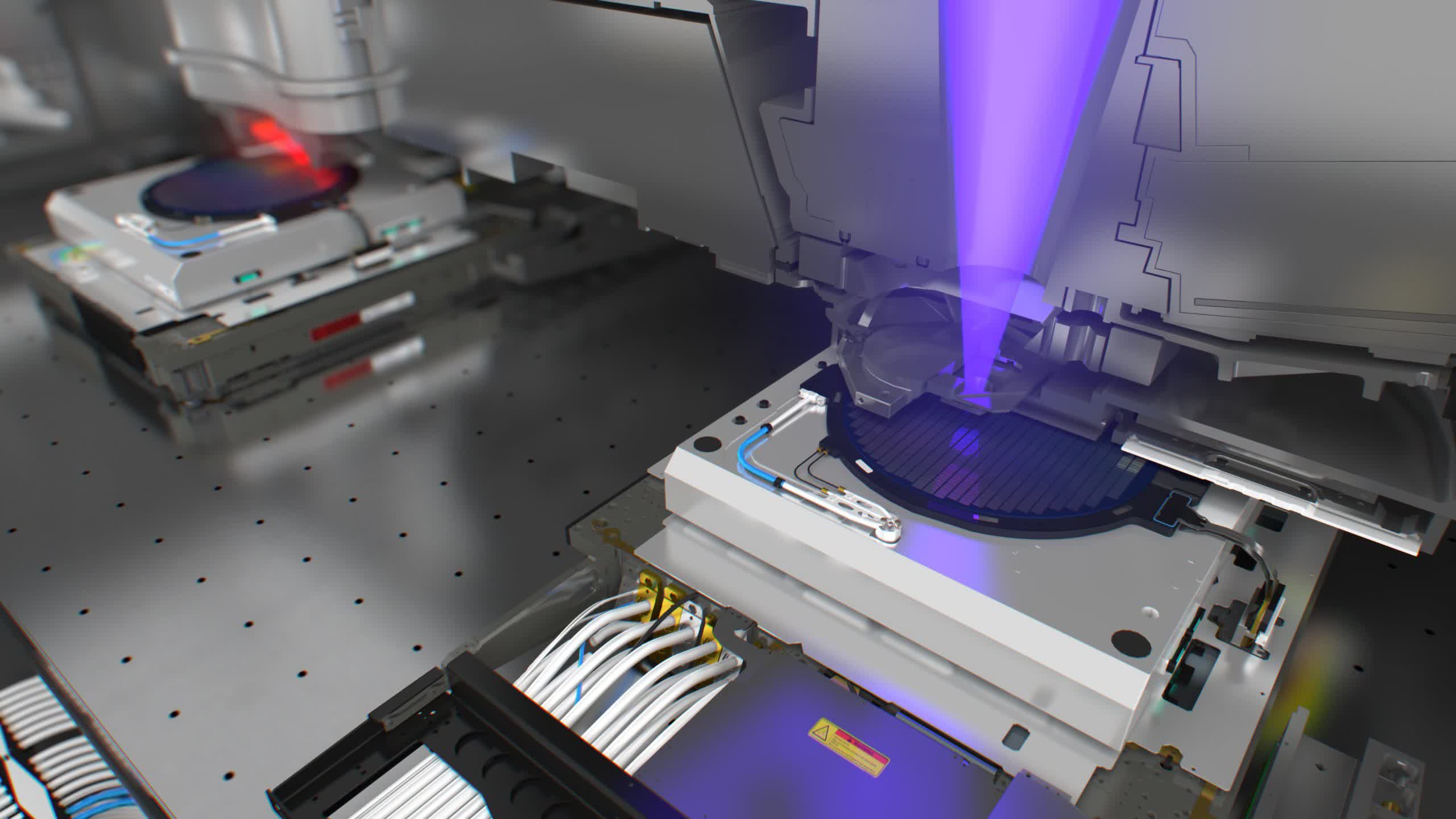

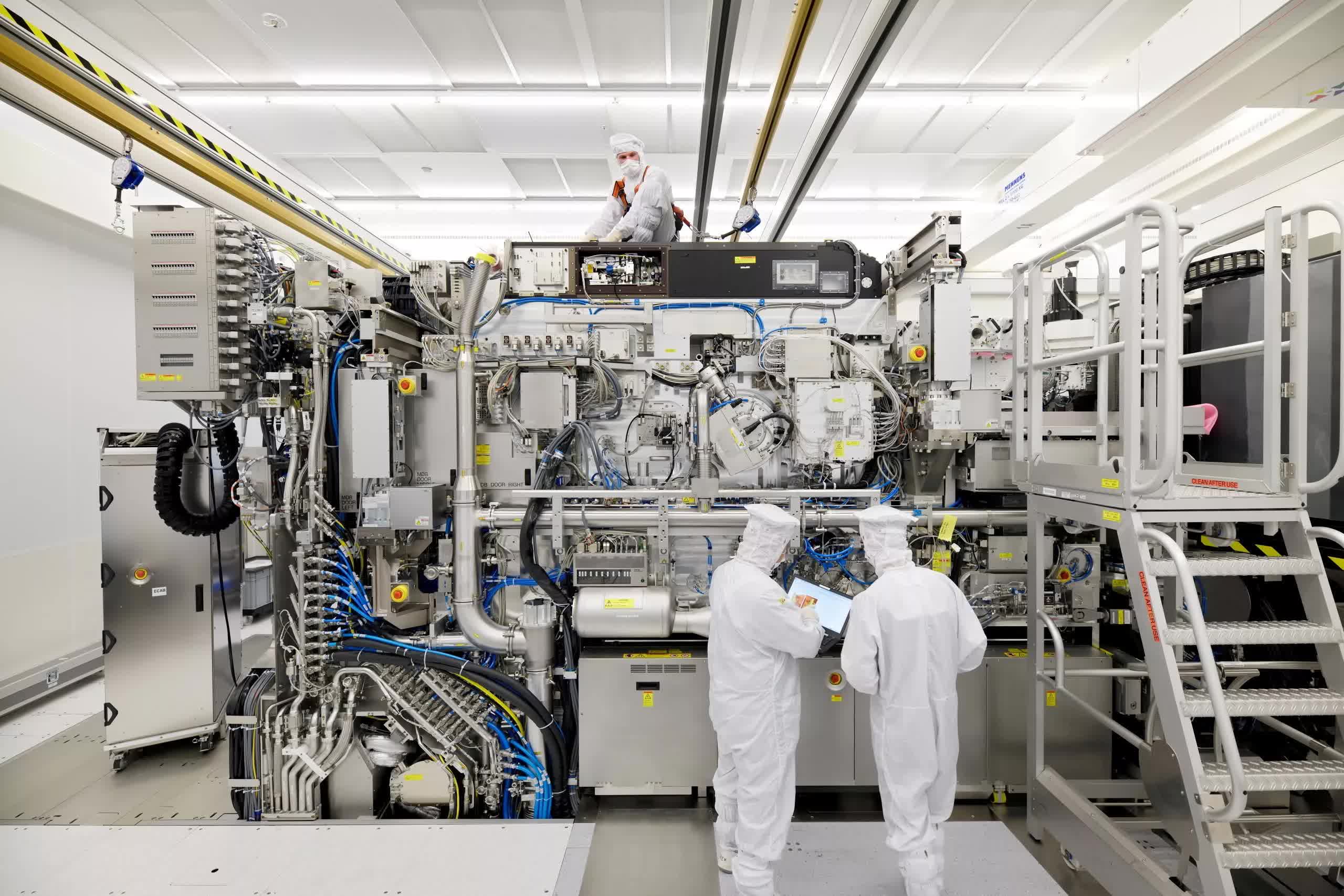

The latest approach targets high-end chips used for machine learning. These are the kinds of chips that can be used to create AI enhancements for search algorithms and finding users who want to watch dancing kitten videos. They are also the kinds of chips that can be used to simulate missile trajectories and nuclear explosions.

From what we can tell, the US government, in all of this, is trying to limit the ability of the PLA and its many affiliates from accessing the latest in US technology. The war in Ukraine has highlighted the US' military advantage rests largely on its access to the most advanced technology. Of course, there is more to it, but this is something that the US military relies on heavily. Seeing China's military as an increasing threat, it makes sense that the US does not want to do anything to help China dilute this advantage.

So in our opinion, the latest switch to banning products marks a meaningful expansion of the US government's efforts. Will this work any better than the entity list?

We are skeptical.

First, as noted above, the biggest force working to dilute past efforts was US companies themselves. Nvidia's shares fell on the latest news, and they warned of a $400 million revenue shortfall resulting from the ban. Maybe this will work for these specific chips, but we think further expansion will meet with stiff resistance from the home front.

Secondly, how will this work in a modern supply chain? Let's say a US company wants to buy a few million dollars worth of banned Nvidia chips. Who will then assemble the chips into working systems, inserting the chips onto motherboards and installing those in server racks? Today, most of that work is done by Taiwanese companies' factories in China. Can Nvidia ship those chips to China? Technically, we think the answer is yes, but it is easy to see how this process can get easily derailed.

Third, this is a short-term move, but it has long term consequences. As we noted above, every Chinese company buying parts from US vendors is now busy looking for domestic alternatives. We have written a lot about the growth in the capabilities of Chinese fabless firms, including a host of companies producing GPUs not too dissimilar from what the US government just banned (not the same, but getting closer all the time). The US government's actions are directly leading to interest in a sea of aspiring Nvidia competitors. For companies like Biren, the US government's actions are a major boost.

And those are just the first order effects. Stratechery recently touched on this, noting that one of Nvidia's biggest advantages in the market for AI chips is its CUDA software. It is now highly unclear what the status of this software is in China. This will certainly increase interest in open source alternatives to CUDA. So not only is Nvidia losing out in direct sales, it now risks seeing its competitive advantage being worn away.

This also extends beyond the GPU/AI semiconductor space, it applies to all US semis, what we would call third order effects. All Chinese companies, even those with absolutely no ties to China's military now have to look for alternative vendors. This is not patriotism, it is just rational commercial contingency planning. The effects are most likely to be felt first in industrial and automotive semis – i.e. far away from leading edge GPUs, as this is the area where China's aspiring chip companies look most competitive today. We are going to keep an eye on companies like Texas Instruments and On semi's comments about China in coming quarters.

So while we understand the US government's interest in curbing the supply of high technology to a potential long-term adversary, we have to wonder if over that long-term this works to China's advantage. There are no simple answers to this problem. That said, the US government needs to think very strategically here. Is the goal to limit specific Chinese military projects? Is it to cripple the entire Chinese semis complex? Is there even an end goal? From what we can tell right now, that does not seem to be the case.