In context: Partha Ranganathan came to realize about seven years ago that Moore's law was dead. No longer could the Google engineering VP expect chip performance to double roughly every 18 months without major cost increases, and that was a problem considering he helped Google construct its infrastructure spending budget each year. Faced with the prospect of getting a chip twice as fast every four years, Ranganathan knew they needed to mix things up.

Ranganathan and other Google engineers looked at the overall picture and realized transcoding (for YouTube) was consuming a large fraction of compute cycles in its data centers.

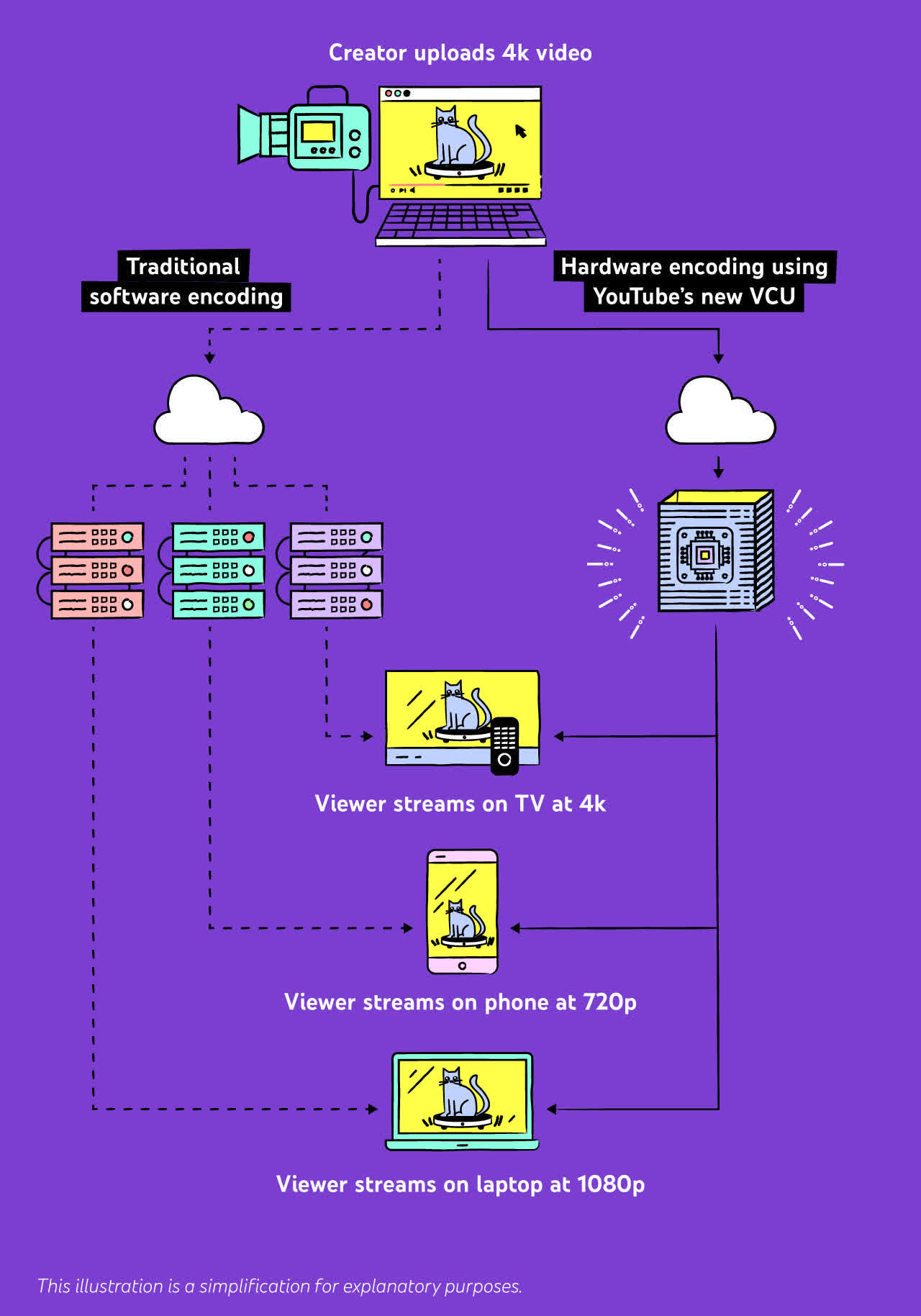

The off-the-shelf chips Google was using to run YouTube weren't all that good at specialized tasks like transcoding. YouTube's infrastructure uses transcoding to compress video down to the smallest possible size for your device, while presenting it at the best possible quality.

What they needed was an application-specific integrated circuit, or ASIC - a chip designed to do a very specific task as effectively and efficiently as possible. Bitcoin miners, for example, use ASIC hardware and are designed for that sole purpose.

"The thing that we really want to be able to do is take all of the videos that get uploaded to YouTube and transcode them into every format possible and get the best possible experience," said Scott Silver, VP of engineering at YouTube.

It didn't take long to sell upper management on the idea of ASICs. After a 10-minute meeting with YouTube chief Susan Wojcicki, the company's first video chip project was approved.

After a 10-minute meeting with YouTube chief Susan Wojcicki, the company's first video chip project was approved.

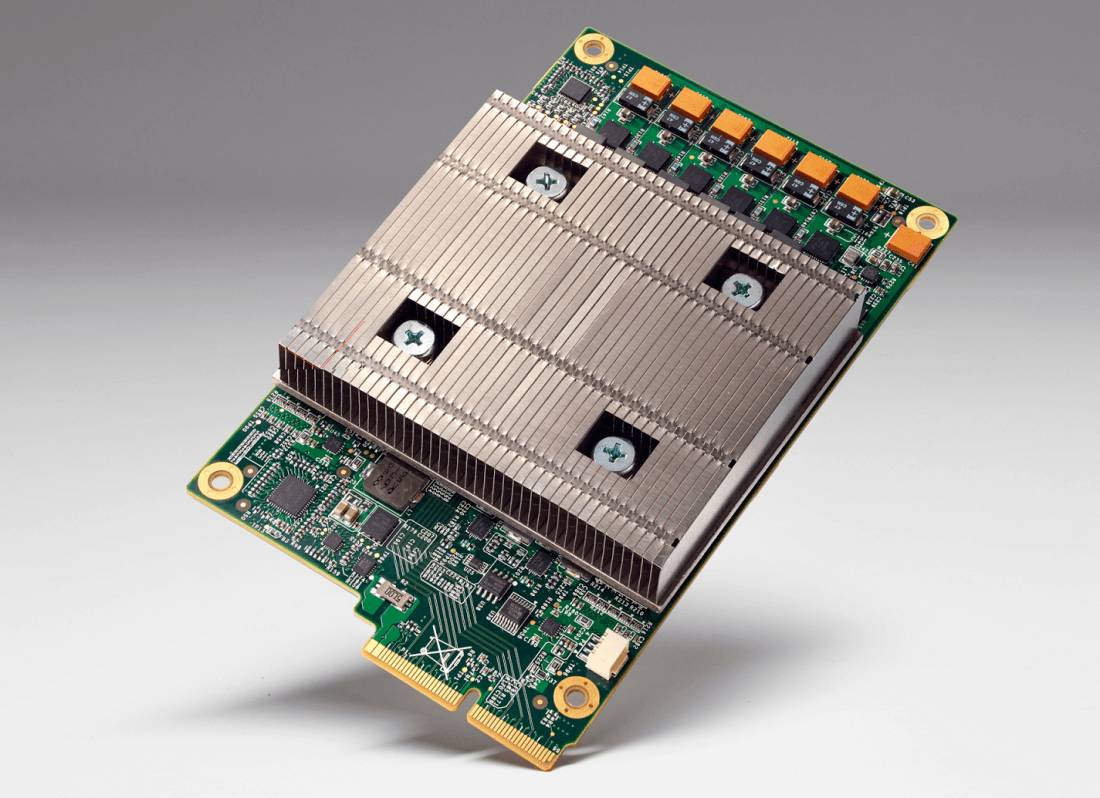

Google started deploying its Argos Video Coding Units (VCUs) in 2018, but didn't publicly announce the project until 2021. At the time, Google said the Argos VCUs delivered a performance boost of anywhere between 20 to 33 times compared to traditional server hardware running well-tuned transcoding software.

Google has since flipped the switch on thousands of second-gen Argos chips in servers around the world, and at least two follow-ups are already in the pipeline.

The obvious motive for building your own chip for a specific purpose is cost savings, but that's not always the case. In many instances, big tech companies are simply looking to create a strategic advantage with custom chips. Consolidation in the chip industry also plays into the equation, as there are now only a couple of custom chipmakers to choose from in a given category making general-purpose processors that aren't great at specialized tasks.

Also read: The death of general compute

Jonathan Goldberg, principal at D2D Advisory, said what is really at stake is controlling the product roadmap of the semiconductor companies. "And so they build their own, they control the road maps and they get the strategic advantage that way," Goldberg added.

Argos isn't the only custom chip to come out of Google. In 2016, the company announced its Tensor Processing Unit (TPU), which is a custom ASIC to power artificial intelligence applications. Google has since launched more than four generations of TPU chips, which has given it an advantage over its competition in the field of AI. Google also crafted its Pixel 6 series of smartphones using a custom-built Tensor SoC, bringing hardware and software under the same roof for its mobile line.

Image credit: Eyestetix Studio