Why it matters: China's government intends to crack down on Uighurs and other Muslim minorities, in what some pundits describe as a "deliberate and calculated campaign of cultural genocide." The country's latest experiment is yet another invasion of privacy that's driven by the idea that we may soon be able to get a good idea of how a person might look by using the tiniest scrap of DNA from them.

China is widely known for its controversial practices with respect to minorities in the Xinjiang region, as well as its strong push for wide adoption of facial recognition systems. The country's latest privacy nightmare is the introduction of new rules that will require anyone who wants to buy a smartphone or a cellular plan to scan their face, supposedly to counter any potential fraud attempts.

The country routinely tests new surveillance systems in the Muslim-dominated Xinjiang region. In November, it started an experiment to determine the feasibility of an emotion recognition system, but it turns out it's willing to go well beyond that with an even more ambitious project that stretches the moral boundaries of forensic science.

According to a report from the New York Times, Chinese researchers have started collecting blood from Uighur Muslims in the city of Tumxuk, where over one million of them are held in detection camps. They want to use the DNA in the samples to try and generate a rough model of a person's face.

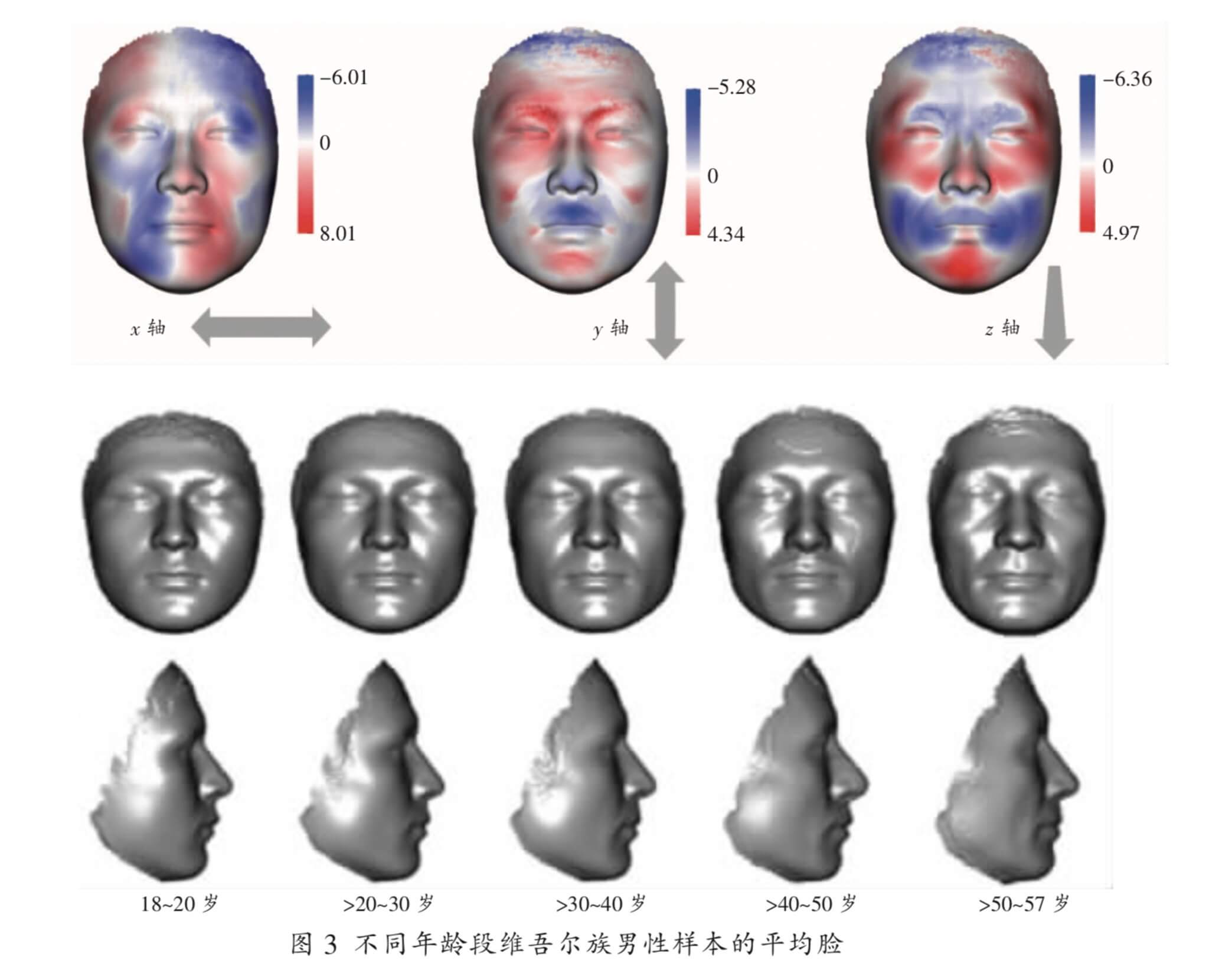

The technique is called DNA phenotyping, and it works by analyzing the groups of genes associated with ancestry, complexion, eye color, shapes of facial features, as well as a person's gender to obtain a sketch of a face that's as close as possible to reality.

Interestingly, the science around this was pioneered in the West, where law enforcement is interested in using the technique to help narrow down the pool of suspects in difficult cases. The same method has also been used to generate models of what ancient humans may have looked like.

The main issue is that even after perfecting their approach for years, scientists aren't confident enough about its accuracy as a tool to identify a certain individual. The current understanding of genes isn't enough to predict how a person might look, and you'd also have to take other variables like age and weight into consideration. The consensus seems to be that we're a long way from being able to use DNA phenotyping as a reliable tool in forensic science.

China isn't waiting, however, and given its penchant for monitoring and controlling its citizens, the new development raises difficult questions about consent and human rights. Mark Munsterhjelm from the University of Windsor, Ontario, told the New York Times the Chinese government is crafting "essentially technologies used for hunting people."

There is no clear indication that the people involved in the research have been asked for consent to provide a sample of their blood, and it's safe to assume that's not the case, since we're talking about internment camps. There are only scattered reports from Uighurs and human rights groups that indicate the authorities have collected blood samples, images of irises, and other personal identification markers as part of mandatory health checks.

Ultimately, the more worrying aspect is the notion that China could use the results of this research to build mass surveillance systems. And according to leaked documents, Chinese tech companies are shaping global surveillance standards, especially in the area of facial recognition - meaning that vision may become easier to export to other regions.