At their recent NextGen event designed to build hype for electric vehicles, BMW announced two: a futuristic, hybrid sportscar and a realistic-looking battery motorbike. At the same event, speaking quietly to media backstage, BMW's board member for development Klaus Frohlich said, "the shift to electrification is overhyped."

BMW had previously announced that they would release twenty-five new electric vehicles by 2025; at NextGen, they accelerated that timeline to 2023. Frohlich only said that "there are no customer requests for battery electric cars. None."

In the numbers:

Presently in Europe, battery-electric sales are up 88% year on year, petrol sales are up 3.1%, plug-in hybrids are down 5% and diesels are down 18%. Plug-in electrics comprise 7% of the market (source).

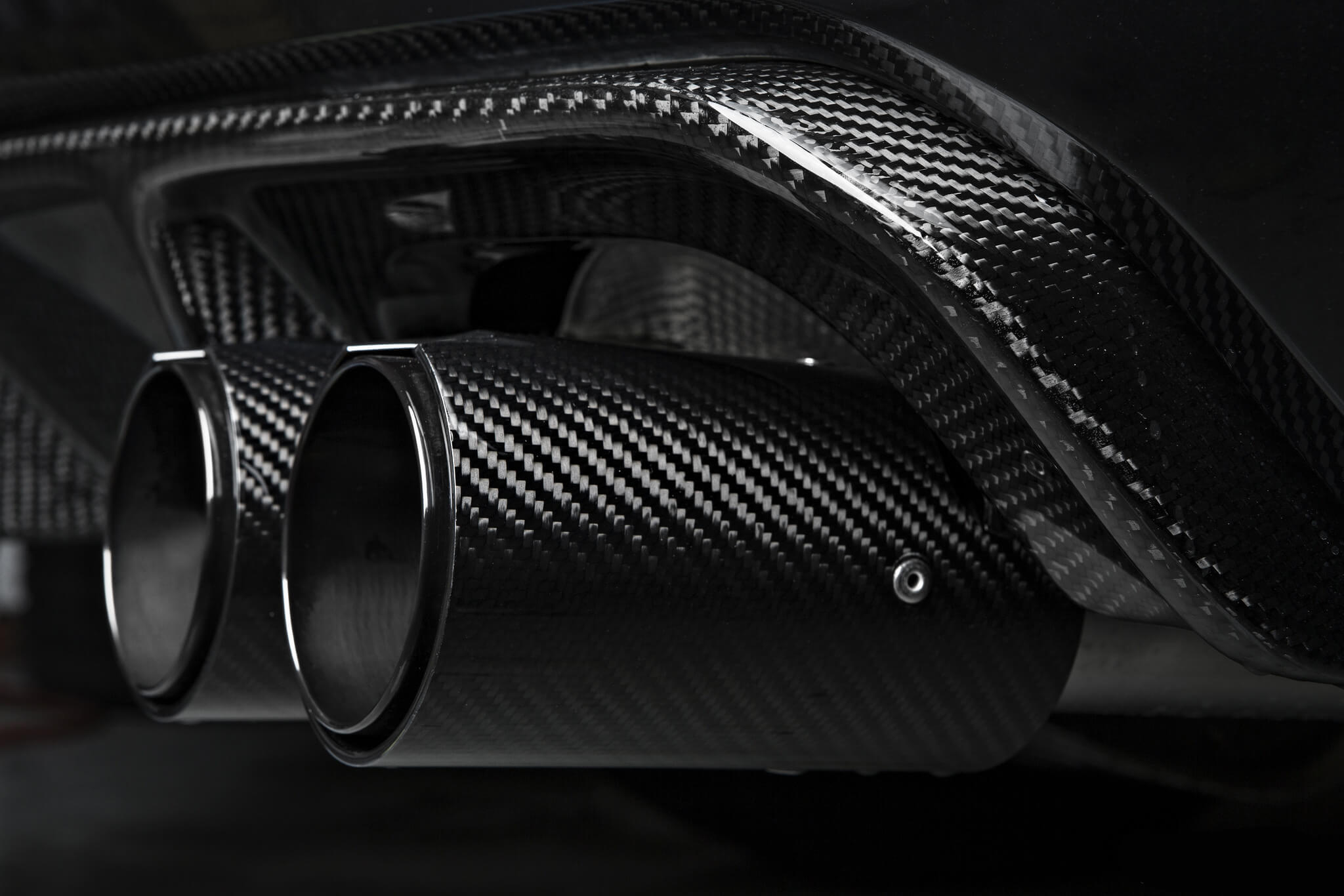

BMW is being forced to stop developing various diesel engines, as they're becoming too costly to redesign each year to comply with environmental standards and new market conditions. Soon to be sacrificed are the 1.5L three-cylinder, turbocharged six-cylinders, and the V12. Frohlich said BMW could replace these models by "flooding Europe" with a "million [electric] cars," but the problem, he says? "Europeans won't buy these things."

Frohlich's apprehension aside, it seems clear that many automobile manufacturers aren't as excited about electrification as their press teams suggest, and that's in the present day. Have manufacturers been silently dreading the end of the combustion era, and could they have already swamped the market with electric vehicles if they'd wanted?

This time two years ago, the European Commission leveled a record-breaking $3.4 billion fine at Volvo/Renault, Daimler, Iveco and DAF for colluding "on the pricing and on passing on the costs for meeting environmental standards to customers" for their diesel trucks. Volkswagen's MAN was also a colluding party, but they were exempted from the fine for exposing the other manufacturers. In April this year, though, Volkswagen and Daimler were caught again, and this time with BMW.

The three automobile manufacturers were accused of colluding to limit, delay and avoid the adoption of selective catalytic reduction systems and Otto particle filters, both technologies designed to reduce toxic emissions from diesel engines found in ordinary cars. The toxic emissions are a large contributor to the pollution associated with tens of thousands of deaths each year, and the only benefit to the manufacturers was profit. The EU is still investigating.

Time and time again, manufacturers have chosen profit over the moral choice and compliance with EU regulation. If electric was less profitable than combustion, it follows that they would be willing to break laws (to a degree) and sacrifice the environment to slow electric adoption. Hint: electric is less profitable.

"[Hybrids] are not more expensive than battery electrics. They are thousands more expensive than internal-combustion cars but we can't charge that to customers and those regulations are reducing our profit pool. We can't have the same margin on those cars. We know. The level is between the internal-combustion margin is halfway more but if we charged the customers for that cost, we would have downsizing with customers going from a 3 Series to a 1 Series," Frohlich said.

Following the most basic doctrine of our economic system, one would expect manufacturers to follow customer demand, and though some surveys suggest a market eager for electrification, others find a social psyche disconnected from reality.

One survey conducted by the American Automobile Association in April found that reliability is the chief concern amongst people shopping for electric cars. This is intuitive; electrics and electronics are frequently the least reliable things in any household. However, this conclusion has no logical or empirical basis: electric cars are far more reliable, it turns out, due to their simplified drive train. While combustion vehicles will have many moving parts susceptible to failure (like gearboxes, in my personal experience) electric vehicles have motors connecting directly to the wheels, cutting out the majority of reasons why you'd need to go to the mechanic.

Most shoppers are also very concerned about safety, with 77% and 60% prioritizing good crash ratings and advanced safety features like automatic braking, respectively. Given the frequency of smartphone's batteries exploding, this concern is also intuitive, yet still not based in reality. The top five most popular combustion vehicles in the US all rank lower than the most popular electric cars in the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's testing.

Despite many shoppers' concerns being unnecessary, there's one very large and real issue that's no doubt on your mind: charging. Let me attempt to describe the European and North American charging networks in the briefest way possible.

Internationally, there are three charging levels: lunch date, dinner date, and overnight stay. That's roughly how long each level takes to charge about 100 miles' worth, but as the date is a car in this case, the least amount of romancing is ideal. Level one (the slowest) is only useful at home and office locations and is more or less ignored by electric drivers on the road, leaving levels two and three.

In both continents there's a ubiquitous level-two charger found plentifully in most cities. In North America it's the J-Plug (J1772, formally) and it's generally configured to 6-, 7- and 11-kW configurations. In Europe and the UK, it's the Mennekes plug (IEC 62196) commonly found at 22-kW, and occasionally at 11-kW and 7-W. Any battery electric that doesn't support these plugs natively will have an adapter available, including the Tesla fleet.

Level three is where it's really at, but unfortunately, it's a horrific mess. There are three competing standards, the Supercharging network developed by Tesla, the CHAdeMO network introduced by Toyota, Nissan, and Mitsubishi, and the SAE Combo CSS network co-developed by Volkswagen, Ford, BMW, and Hyundai. Not only are these networks not cross-compatible (except for Tesla vehicles which can charge off CHAdeMO with a $450 adaptor), but even amongst a single network, they're horribly inconsistent with speeds.

All three networks are generally equally common, meaning if they'd been standardized from the beginning, each battery electric would have two to three times as many level three charging stations available right now. Logic and experiments confirm an average person is significantly more likely to go electric if there are numerous fast chargers in their area. But that's not the only ridiculous error dissuading buyers from electrification.

"I couldn't do a test drive because the key was lost. I was encouraged to purchase a non-electric vehicle instead."

- Louise A., at a Nissan dealership in Connecticut

In 2016 the Sierra Club sent undercover volunteers to 308 car dealerships in the US, to highlight the differences between how a salesperson acts with an electric vehicle versus a combustion one. The results were staggering: one in six dealerships told the volunteers their electric cars were not sufficiently charged for a test drive, only half the salespeople described how an electric is charged (or refueled for hybrids), and one third did not discuss the tax incentives. In 2016, that incentive was usually $7,500 in tax credits.

"There were no EVs in stock and he stated that he has no interest in ever selling an electric vehicle... He said that the only way he would sell an EV is if Volkswagen forced him to."

Tony G., at a Volkswagen dealership in Maine.

A separate study published by the National Academy of Sciences in 2014 found buyers looking at electric vehicles were consistently less satisfied with their experience than those looking at combustion vehicles. Ratings on a buyer satisfaction index score show plug-in vehicle buyers were 94% as satisfied as non-premium combustion buyers and 88% as satisfied as premium combustion buyers. A notable exception was Tesla, whose customers were highly satisfied.

There are two clear reasons why dealerships aren't very good at (or are outright hostile to) selling electrics. For starters, like most of the population, they have a poor understanding of the technology and are unable to discuss it and will shift customers to familiar ground. And secondly, as mentioned above, electric vehicles require far less maintenance and in a world where dealerships make half their profit in maintenance fees, that's a disincentive.

The bottom line is this: many manufacturers and dealerships are holding electrification back in the name of profit, and customers are afraid of electric cars due to common misunderstandings. Had all this been resolved a long time ago, who knows how many electric cars might've been on the roads today.