Bottom line: I strongly feel that self-driving vehicles will be remembered as one of the greatest technological achievements of the modern era. I'm an even firmer believer that we're about to open Pandora's Box without fully considering (or even realizing) the impact that it'll have on seemingly unrelated segments of society.

Personal transportation in a world void of human drivers will presumably be much safer, right? That's great, but it also means that a lot of people are going to be without jobs. Insurance companies won't need nearly as many claims adjusters, the DMV won't need to be nearly as large as it is today, police forces could be greatly reduced and as morbid as it sounds, hospitals won't need as many doctors (in 2012, motor vehicle collisions sent nearly 7,000 Americans to the ER each day).

With fewer people dying in auto accidents, there won't be nearly as many organ donations, meaning that some sick people who might have survived thanks to a transplant won't live as long. It's a seemingly endless chain reaction of cause and effect.

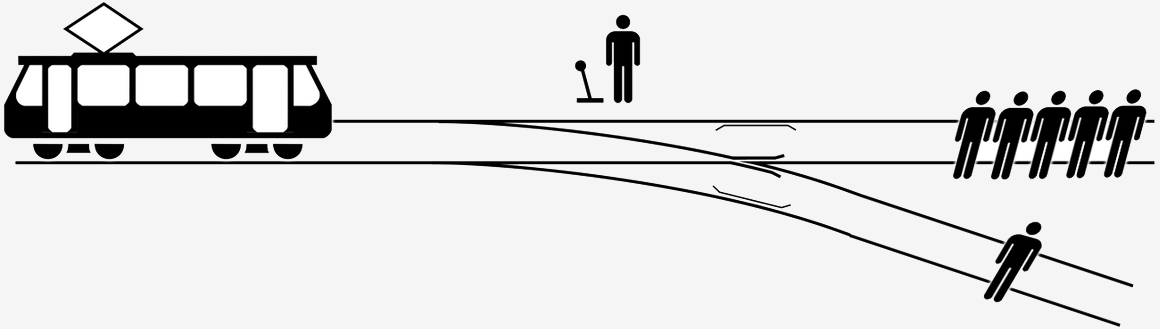

In some instances, however, there will be casualties. Take the Trolley problem, for example.

In this common thought experiment, you see a runaway trolley racing down the tracks towards five people. You have access to a lever that, if pulled, will divert the trolley to another track where it kills just one person instead of five. Do you pull the level and spare the lives of five people by sacrificing one? How do you justify that decision?

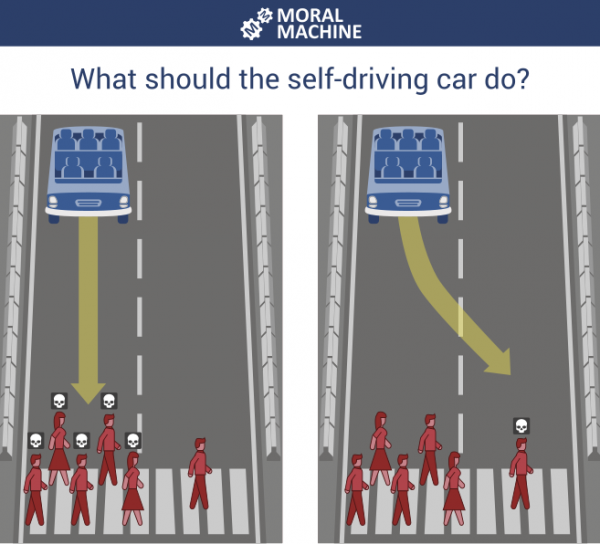

It's inevitable that self-driving cars will have to make similar decisions at some point. To gauge public perception on global moral preferences, researchers at the MIT Media Lab in 2014 launched an experiment called the Moral Machine. It's a game-like platform that gathers feedback on how people believe self-driving cars should handle variations of the trolley problem.

Four years later, the project has logged more than 40 million decisions from people in 233 countries and territories around the globe, highlighting how different cultures prioritize ethics.

The test focused on nine different comparisons including how a self-driving car should prioritize humans over pets, more lives over fewer, passengers over pedestrians, young over old, women over men, healthy over sickly, law breakers over lawful citizens, higher social status over lower and whether the car should swerve (take action) or stick to its course (take no action).

The results are fascinating, if not a bit stereotypical. In countries with more individualistic cultures, a stronger emphasis was put on sparing more lives, perhaps due to people seeing the value in each individual. In regions like Japan and China where there is a greater respect for the elderly, participants were less likely to spare young over old.

Interestingly enough, Japan and China were on opposite ends of the spectrum with regard to sparing pedestrians versus passengers. Those in Japan would rather ride in a car with a greater emphasis on sparing pedestrians while those in China were more concerned about the safety of a vehicle's passengers.

Edmond Awad, an author of the paper, said they used the trolley problem because it's a very good way to collect data but they hope the discussion of ethics doesn't stay within that theme. Instead, Awad believes it should move to risk analysis - weighing who is at more risk or less risk - versus who should or shouldn't die.